Inheritance

A photograph at the end of an era

The photograph is grainy, shades of grey and sepia. The hills of Happy Valley look strangely bare for anyone who knows it these days, a dark backdrop against which, in the centre, is the photo finish: a blur of six or seven horses with Heavenly Hope being pipped, by a nose, by This Year’s Luck.

In the foreground is the crowd, pressed up against the barriers, their backs to the camera as they cheer on the horses. Except for one. Hands in his pockets, turning back towards the camera from under his hat, one man’s pale face can be seen.

I’ve looked and looked again, and I’m almost certain it’s Morgan. His face is hard to make out, the features smudged. It would be a strange thing to do, to turn and look back, just as This Year’s Luck edged ahead in the final couple of furlongs, to beat Heavenly Hope, a horse on which he’d put everything. But while you can’t really make out his nose and mouth, there’s a feeling I can’t shake as I look at him, at the very split second he lost it all: it seems to me that he’s smiling.

The photograph came to me as one of three, a mystery package that appeared in my mailbox one Tuesday in an unmarked square white envelope. One of the other photographs is a family portrait, the whole Mau clan, including sufficiently high-ranking in-laws, represented by at least four generations arrayed in two rows. The other is a landscape shot, part of a fishing village, an inlet between two sloping spits of land folding together, a path curving away to the right in front of the sea, and a couple of small boats on the water to the left.

They brought to mind other photos I’d seen, photos of photos on the walls of the old family home on Peak Road, now long since sold off. Ranks of Mau grandees filling the front and centre, with the few remaining Frobishers pushed out to the margins. Through the 1920s and 1930s, Grandma Luisa and Grandpa Frederick (my great-great grandparents) are the focal point, her stone-faced, him confident in his waistcoat and tie. From the late 1940s onwards it’s Luisa at the head, with Uncle Donald invariably on her elbow, towering over her. Sara is next to him in the earlier ones, but never much of a presence, and alas she also disappears in the early ’50s. From then on, it’s Luisa and Donald holding firm in the middle, the two pillars of the family in its final generation of glory.

I’d never seen the family group shot or the fishing village, but the horses and the crowd were familiar from somewhere. I picture Grandma Luisa in the parlour, venting at the photo:

“This Year’s Luck! This year’s ruin!”

The image and the date are burned into Mau family lore: 9th February 1955, fifth race on the card, in which the fortune built by the family over a hundred years was lost at the moment This Year's Luck nudged ahead of Heavenly Hope.

She was long gone by the time I was born. But still I sense her fury as I look at it:

“A hundred years!”

Behind Luisa, the decades are arrayed on the wall. But the end of it all was captured in another image of one instant, the one that came to me in a plain white envelope.

In reality, though, it wasn’t the horses that cost us everything. Morgan knew that the races were too visible, and he was too well known, so he kept his bets small, jumped up and down when his horse came in and, more often, tore up his ticket and threw it in the air with an exasperated “It was a dead cert!” each time he lost. He liked a flutter, it was known. Just Morgan having his bit of fun.

Were the races where it started? Who knows, but in the early ’50s, as Uncle Donald trusted him with larger portions of the company, the business trips to Macau became more frequent. Maybe the first was meant as a one off, perhaps with a lover, the same feeling as skipping school. Chips down on the table; what harm can a little flutter do? By the end, it was often enough that he was greeted by name in the gambling houses, at least until he was no longer welcome there and had to, by some accounts, ask for credit at the less reputable establishments. But Uncle Donald hadn’t seen it coming, and as he handed over more control to Morgan, the debts must have mounted.

He hid it from Uncle Donald. He hid it from everyone, even Luisa’s Medusa gaze. And when This Year’s Luck crossed the line a nose in front of Heavenly Hope, he turned away from the track and instead of his usual, cheerful ticket-tear and throw, Robert later told us, he just placed his hands in his pockets, raised his eyebrows, and said:

“Well, that’s it.”

Nobody knew what he meant. But he couldn’t be found the next day, or the day after and neither could Nellie, a distant cousin (no blood relation, but only nineteen ). Those were the first inklings of trouble, and then the phone calls started. Then more calls from creditors, and when Uncle Donald – by now not as sharp as he used to be, but he still knew the business – and Robert went into the books, going line by line through Morgan’s looping cursive, with its flourishes on the tails of the 2s and 3s and its long, hanging 7s, they could only stare helplessly at the stark, dwindling figures as the phone rang and rang behind them.

There was something about the photo finish that wouldn’t let me go, and not just its status as an anti-icon, the moment of our dynasty’s fall. I sat with it over a long beer one evening, puzzling over Morgan’s odd maybe-smile. But there was also the photo itself, grainy black and white, when a family like ours could have afforded – would have made a point of affording – a colour camera. And in fact I could recall clearly various Mau photographs in technicolour from that last, post-war decade. Frederick was gone by that time (too confident as it turned out; the Japanese couldn’t be reasoned with), and Sara went early to cancer, but there are other uncles and aunts posing in yellows and mauves on the Peak. And there’s Robert, the only one still around, one of those prematurely middle-aged children, serious in his royal blue blazer, but already defeated.

It was only a few days later, pressed among commuters in the MTR, somewhere between Hung Hom and Mong Kok East on my way to Introduction to Macroeconomics, that I had a lightbulb moment. Surely, I thought, they have to keep records of photo finishes at the races. In case of disputes about winnings, things like that. And anyway someone had to have taken the photo, surely they must keep copies, even from the pre-digital ’50s.

I found a number for the Happy Valley Racecourse, called it, and was passed around for a while before they referred me to a Mr. Lau in the Archives Section who might be able to help. Two days later, a Thursday evening, I found myself walking past Hong Kong Football Club and round the corner towards the blank rear of the main grandstand, towards the site of my family’s ruin.

Mr. Lau received the photo from me with two hands, set it gently on his desk, raised his glasses – held around his neck by a thin silver chain – and placed them on his nose. First through the thick lenses, then over them, then through them again, he subjected it to his scrutiny. He picked it up by the edges and tilted it toward him, the light from the fluorescent ceiling strip catching it at this angle. Then he laid it back down, sighed, removed his glasses and let them hang. He regarded me steadily.

“Photo finish, you say?” he said, with what I felt was a hint of accusation.

“Yes,” I said. “Isn’t it?”

He turned the photo towards me.

“Which horse winning?”

It was my turn to lean forwards. This Year’s Luck had beaten Heavenly Hope, of course, a fact carved in stone in family legend. And of the front two horses, I’d thought This Year’s luck to be the nearer of the two to the camera, but looking again, I strained to separate the blurred muzzles of the two frontrunners.

“It’s not that clear…” I said.

“Not clear at all,” he said. “Not much good for photo finish.” He pushed himself up from his chair, opened a drawer at the far side of the room, and pulled out several stills which he dropped in turn on the desk in front of me. “Photo finish needs to be clear.”

Indeed, each of the black and white images in front of me captured a split second in perfect clarity, the nose of each horse measurable against the others along the white vertical line of the finish. I was probably frowning.

“This isn’t photo finish,” he said, picking up my photo. Then pointing back at the stills he’d dropped, he added: “Look at these. No crowd.” Turning his attention to my photo again, he tapped the pale face, which was possibly smiling, of the man who may or may not be Morgan Mau. “In yours the less blur part is this man.”

The face was hard to make out, but compared with the fuzzy mess of the horses and the limbs of the other spectators, it now appeared to me as the still centre of the image. Mr. Lau continued, “If I have to guess, I don’t think it’s photo of horses.” He held his nicotine-stained index finger just under the pale, turning face. “It’s photo of him.”

Back in my apartment, I looked at the family photo again, trying to match the man in the non-photo-finish shot with the image of the man who is definitely Morgan.

He’s in the back row, all the way to the right. There’s a bit of a gap between him and the next family member, a middle-aged woman who I don’t recognise. Nellie is in the front row, in her early teens I’d guess, so slight she’s barely there except for the chunky camera hanging around her neck. Perhaps a recent birthday present that she poutingly refused to relinquish for the photograph? She has a look of defiance, as if challenging the photographer to do better with his than she knew she could with hers.

Why Morgan rather than the horses? And why black and white rather than colour?

Wong’s camera shop felt like a time capsule. When I opened the door, the movement triggered a small brass bell. At first I’d thought the shop was empty. A few rays of light came through the shuttered windows, catching the dust floating on the air in the long room. Vintage cameras of various shapes and sizes sat on the shelves that lined the small room from waist- to shoulder-height.

I started when I caught movement at the far end. As my eyes adjusted, I made out the figure of a man I assumed to be Mr. Wong. “Can I help you?” he asked in a voice clearer and louder than I expected in the silence of the shop. When I told him I was looking for help with regard to an old photo, he stood quickly, took it from me with much less ceremony that Mr. Lau had done, and stood over it. With his two hands placed palms down either side of it, a bright desk lamp illuminating the image, he said, “Taken in 1955, you say?”

“Yes,” I said. “As far as I know.”

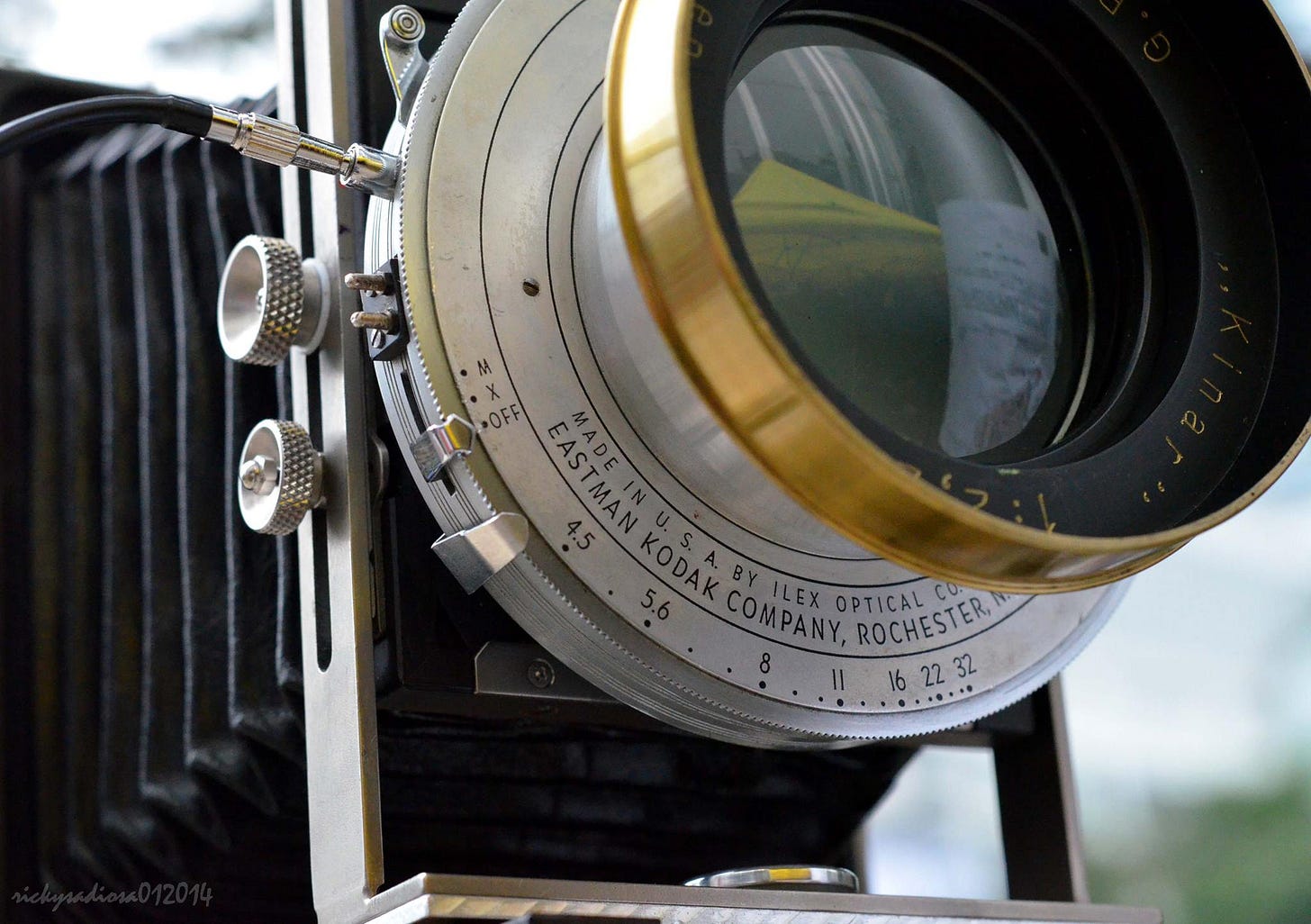

“Well, it isn’t typical for 1950s photography,” he said. “You had colour by then, and hand-held cameras, even though they were heavy.” He took a few steps out from behind his desk, squeezing past me, lifted a camera from one of the shelves and handed it to me. It was black, weighty, with a metal lens and bezels on the top. “You could get a sharp enough colour photo with one of these,” he said. “Not cheap enough that everyone was running around with one, but not an unheard-of luxury either.”

“Strange,” I said. “They would’ve had the latest thing, I’m sure. And I’ve seen colour photos…”

He shrugged. “Well, either the photo is older than you think, or it was taken with some sort of vintage model.”

“Wait,” I said, and went into my bag for the family photo. I laid it on the desk next to the not-photo-finish and pointed to Nellie and her chunky camera round her neck. “Something like this?”

“Ha,” he said, strode across the room, and grabbed another camera with both hands which he then thrust at me. “Something very much like this.” It was one of those old cameras with a sort of black, leathery concertina lens coming out of the box that you held. “Kodak six-16,” he said. “Early 1930s.” He pointed back down at the blur of Happy Valley, the horses, the moment it all collapsed. “And it’d give you something like this.”

So rebellious Nellie, now nineteen and old enough to know her mind (or at least so she thought), takes her favourite vintage Kodak to the races, has it at the ready, follows This Year’s Luck and Heavenly Hope as they go neck and neck down the straight … then pans ahead to Morgan, holds him steady through the viewfinder – no casual quick snap with a Kodak six-16 – as he faces her, smiling? Behind him, two horses cross the line a split second apart and in doing so bring down a dynasty of generations, but there’s Nellie taking a picture of Morgan, calm as you like. Almost as if … it was all part of a plan?

I met Robert one evening in Causeway Bay (“It’ll have to be after work – at lunch they barely give us time to shovel a bowl of rice down our throats”) and we struggled with the initial pleasantries while sidestepping our way through throngs of shoppers, with traffic and adverts blaring all around. We looped our way out of the back of the shopping streets, and after a few twists and turns we were among the quieter low-rises of Tai Hang where he pushed open the door to a small bar.

He slipped off the shapeless black jacket and nodded to the barman, who set a bottle of Gweilo in front of him almost before we’d sat.

“I’ll have the same,” I said, as the quiet and the weight of the coming conversation filled the room. He met my initial questions with short replies, rubbing his eyes and sighing, and giving every impression that he saw the whole thing as a waste of time.

“He cost the family everything and now his name’s mud. What else is there to say?”

For the first twenty minutes, I made no headway and was thinking about how best to beat an honourable retreat when I first mentioned Nellie. Immediately he sat back, his face and upper body relaxing, as he looked towards the ceiling.

“Ah, Nellie.”

A soft spot?

He took a long swig from his bottle, emptying it, and held it up to signal for another. He leant forward, although he looked towards the wall rather than me.

“Nellie was an interesting one. You know her mother was an adoptee? An orphan back in Lancashire. A branch of the Frobishers took her in before they came out to Hong Kong. I’m hazy on the exact details but yes, Nellie wasn’t actually blood to either the Frobishers or the Maus. They all treated her well enough as far as I know, apart from the usual snobbery. I mean, she wasn’t made to scrub the floors while the other sisters went to the ball or anything.”

“So what was her relationship with Morgan?” I asked.

“That’s the question,” he said. “You can imagine the rumours. She was pregnant, they had to hide it, et cetera. But I don’t go for that theory because there are ways of dealing with that kind of thing without bringing the entire family down. Or that she was after Morgan’s money, and somehow the gambling was part of an elaborate cover for them to take off with a chunk of the Mau family fortune. But I don’t buy that either.”

“Why not?”

“Well, when Donald went into the books, everything was documented. Morgan hid his gambling and the losses, but he hadn’t been sloppy about the bookkeeping. In fact, it’s almost as if he wanted us to see where every last dollar had gone, sort of rubbing salt into the wound …”

“But?” I said.

“But. I don’t think he and Nellie ran off with chests stuffed full of cash. You see, the thing about Morgan was he hated the money. People assume he must have been greedy, or flash, but as far as I can see he never was. Entitled maybe, as much as anyone born into money is – he never had to set his emails to send on a three-hour delay to pretend he was still working up to bed time.”

He half-lifted his phone, as if the weight of his inbox was too much to think about.

“But he wasn’t one to be driving around in a Ferrari or buying Prada handbags for some fancy piece, or even expensive suits for himself.”

“So he wasn’t flashy.”

“No, he wasn’t. But it was more than that. I mean, he hated it. You know, it was only one comment I overheard. But sometimes just one little thing tells you an awful lot about someone. And when I think about everything else he did in light of that, it all makes some kind of sense. More than the pregnancy theories anyway.”

“And what was the comment?”

“I was only a kid at the time. He and Uncle Donald had taken on a new accountant. Some smart-looking fresh graduate. Not sure if it was his first day, but he was brand new and they were showing him the ropes. Donald had this ritual of inviting new employees to tea in the house on Peak Road, to show them the grandeur of the Mau empire they were entering as a mere foot soldier, I suppose. I must have been pottering around the place while all this was going on.”

I pictured Donald, puffed up in front of the gallery of photos, explaining when the first Mau warehouse was opened, how much they made in the 1890s, the size of the company by the time Frederick took the helm, and so on. Going through the whole history of the Maus, who stood arrayed on the wall, their faces proud, stern, sometimes awkward and, in Morgan’s case, what?

Robert drew breath for what I hoped would be the revelation.

“My memory is of them standing together, looking out of one of the big windows with the view down over the harbour. I’m not sure if I’d been creeping around or if Morgan just didn’t care who heard him. But he said to the accountant, ‘You know how the Maus got their start?’

“The accountant either had no idea or knew he wasn’t supposed to answer, so Morgan carried on. ‘It was Frobisher money, originally. The Maus married into it, then sort of out-bred them and took over.’ He didn’t speak bitterly, exactly, but more sharply, as if he wanted to hack down a tree blow by blow. I imagine the accountant must have been pretty uneasy, but Morgan pressed on. ‘And do you know how the Frobishers got their start?’”

Robert looked at me at this point, as if I had become that accountant by the window in the house on Peak Road eighty years before.

Like the accountant, I sensed that my job was to keep quiet and wait for the answer.

“The Frobishers,” said Robert, “had interests in India and South China.”

He cleared his throat, giving me a chance to interject. I had no idea what might be expected, so I allowed him to continue.

“And how do you suppose a British business made its money in Canton in the late eighteen hundreds?”

Again, he looked up at me, and again I waited.

“Let me give you a clue,” said Robert. “It wasn’t cotton. And it wasn’t tea.”

“Ah,” I said.

“So you see,” said Robert, “Morgan hated it all. Didn’t want any of it.”

Morgan Mau, gambling away the family fortune, not out of addiction or greed, but to wash away the stain?

“You think he lost it all on purpose?” I asked.

Robert shrugged, looked away again. He was no longer reflective, just closed off. Then he picked up his phone and gathered his jacket in a bundle under his arm. “Delayed-send emails to write,” he said, stood, nodded at the barman, and left me with the check.

I laid the three photographs out in front of me again, although the fold-out table in my Jordan walk-up wasn’t big enough to set them out without overlapping them slightly. If Morgan Mau had bet it all on This Year’s Luck rather than Heavenly Hope, would I be gazing down from the Peak, lording it over Victoria Harbour and the rest of Hong Kong Island rather than standing at a plastic table, looking through a tiny window at the laundry hanging a few metres away on the other side of Parkes Street?

Here was Morgan, the two horses and the rest of the pack in a blur, the not-photo-finish, a split second in Happy Valley, the moment the cracks in the dam gave way and a torrent of debt buried a hundred-year dynasty. And here were the generations of Maus and Frobishers, and Nellie and her camera.

And there was the third photo, shades of indistinct grey – taken, perhaps, with a 1930s Kodak six-16 – a view of a fishing village, the shot completely empty of people unless someone was hidden from sight aboard one of the two fishing boats or in one of the houses.

The third photo looked back at me, mute. It could be any of those fishing-type places. Cheung Chau or Lamma or Tai O. Or somewhere in the New Territories, out Sai Kung way. Despairing of pinpointing a location from a single image, I turned to Google.

“How to work out location from photograph,” I typed.

Google duly led me to a game called Geoguessr, which requires you to do exactly what I was attempting: from the ground-level photos taken by Google’s roving cameras, you have to work out where it is and put a pin on the map, and the closer your guess to the actual location, the higher your score. From there, the internet funnelled me to YouTube and to various Geoguessr channels, where expert players are able, from just a single still, to drop their pin within a few kilometres of the correct spot.

“INSANE score on Geoguessr.”

“Best Geoguessr game EVER (no moving attempt)!!”

I watched Geoguessr videos deep into the night, picking up hints and tips, how to scan roads signs for alphabet and language, to check which side of the road any cars are driving on, to look for brand names on adverts, the angle of the sun, distant mountains and other features.

I waited for morning and better light to look at the third photograph afresh. I tried to unsee, not simply to affirm what I’d already thought I’d seen, and to come at it as if for the first time. With soft eyes and a strong black coffee, I scanned it again, trying to allow new details in. There was still an inlet, with a couple of fishing boats and a shore-side path curving off to the right and out of shot.

I allowed my eyes to drift out of focus, and in doing so the blur of the sea and the horizon became a little more than a blur, the grey a bit heavier, a smudge of something between water and sky? Land, perhaps?

I looked at the shadows cast by the boats and by the stilts on the jetty. They had some length to them, so it was taken in the morning or evening, and the shadows were coming roughly towards the position of the camera. So if it was morning, the photographer (is that you, Nellie?) was facing east, and if evening, facing west. Instinct, and perhaps the softness of the light in the photo – although that might just have been the age of the camera and the photo – told me it was evening.

Evening, facing west from a fishing village, with land in the distance? I zoomed in and out of the map on my phone, scanning across Hong Kong Island, Lantau, and up into the inlets of the New Territories. From somewhere on Lamma across to Lantau, maybe? But that felt too close for the smudge on the horizon. Some part of Sai Kung, facing back in across a bay, also seemed too tight. Was it one of those tiny, impossible-to-get-to islands? Again, none of the distances and angles quite seemed to work.

Looking up, I realised I was hunched and tense, and leant back while loosening my neck and shoulders. I inadvertently zoomed out from my map as I did, bringing into view the whole of the Pearl River region, the string of cities running counter-clockwise from Hong Kong: Shenzhen, Dongguan, Guangzhou, Zhuhai, and finally Macau.

Morgan Mau and his Trips to Macau. It has the ring of a nursery rhyme to be passed down the generations as a warning against profligacy and degeneracy. In another world, the one where Heavenly Hope kept his nose in front for a split-second longer through the last furlong, Grandma Luisa might have sat a few-months-old member of the clan on her knee and chanted it into the child’s ear. She would have meant it as a joke, mostly, but the incantation would have carried with it the threat of a hundred years of misfortune should her wishes be disobeyed.

As it was, the curse struck before the warning could be given and Morgan Mau’s trips to Macau weren’t discovered until too late.

With a start, I looked back at the photo. Was the dark smudge in fact Macau, or even mainland China? Part of Macau or Zhuhai in the distance? Morgan no longer had the funds or inclination to jump on the ferry, but was happy to sit in… well, wouldn’t that make it Tai O? Was he looking out at the sun setting over the hopes and dreams of the Grand Lisboa and the Cotai Strip?

I had a full week of revision classes before end-of-semester exams, so it wasn’t until the following weekend that I was able to take the MTR out to Tung Chung. A Cathay-liveried flight was taking off ahead on the right as we came into the station. I took the minibus on to Tai O.

I found a spot for a coffee first, and drank it with the photo in front of me, now feeling impatient and regretting delaying my search. As the lady running the café came past and glanced at it, I thought to ask her if she could help me. She squinted at it, then shook her head.

I walked around the village, looking out west, mentally removing houses that could have been built since, trying to see through them for the right arrangement of hills, water and coastline. Getting hotter and sweatier, I stopped to ask for help once or twice, but received only more uncertain squinting, more shakes of the head. I walked out of the village, up a hill and onto a promontory, then down the other side and paused between a couple of houses. I took off my backpack and unzipped it to take out my bottle of water. I took a swig, then another, and replaced the cap. Then I looked back up, and there it was.

The hills coming down on either side, the path curving away to the right. Land visible across the water to the west, a couple of houses along the path and a few fishing boats bobbing on the swell.

There were only three dwellings at this junction in the path, fewer than the impression given by the photo. One was now obviously derelict, while the other two stood in silence.

I opened the gate to the one on my right, the one closest to the position where the photo would have been taken. I walked up the path, noting small beds of flowers and herbs on either side, and knocked on the door, unsure if I wanted anyone to open it. I was met only by silence. As I bent down and to my right to try to see through the window, I jumped at the sound of a door opening behind me.

An ancient woman, like a gatekeeper of classical myth, stood staring at me.

“I’m looking for someone,” I said, holding the photo up before realising that there was nobody actually visible in the picture; anyway, she made no attempt to look at it.

I put my cards on the table.

“I’m looking for Morgan Mau,” I said. “And Nellie Frobisher. I’m Morgan’s grandson.” I produced the two other photos, which she also ignored as she came towards me, pushed past me, and drew from her apron pocket a key which she jiggled and turned in the lock.

She pointed towards the door handle and withdrew.

I expected the door to creak open and to have to push my way in through spiders’ webs, but it swung inwards in silence.

More light was coming into the room than I expected. I felt the weight of time there, but the space was clean and neat.

The first thing I saw distinctly was the camera, and then I knew for sure. Sitting on a small round wooden table in the far corner was one of those old cameras, one of the ones with a sort of concertina lens coming out of a box that you held. A Kodak six-16.

Then I saw, on all four walls, the photographs. All grainy sepia, the story of two lives unfolding around the room.

There they are, young and still freshly on the run, both sporting new haircuts, Morgan in a short-sleeved shirt and Nellie in a plain summer dress. Here they are, standing in front of the house, one on either side of the door. Many images contain only one of the pair: Morgan bending over the plant beds in the garden, Nellie holding up a small birthday cake.

As I worked my way around the room, and even though the trusty old Kodak and photography plates smooth out the wrinkles, they nevertheless age, degree by degree. Nellie leaning on Morgan’s shoulder, a little tired around the eyes; Morgan with his hands in the small of his back, stretching after a spell with his plants.

In one, and one only, they become bolder, Morgan mugging for the camera – “I really shouldn’t be here, should I?” – in front of the art deco curves of the Grand Lisboa. Apart from that, they never seem to stray far from the house in Tai O, tending the plants, sharing meals, walking out along the path towards the sunset, as the years tick by.

The decades arrayed on the wall, and the coming end captured in the images of a series of instants. On the final wall, to the right of the door where I came in, there comes a point when there’s no more Nellie. In the last image of her, they’re together, her head on his shoulder again, her eyes gentle. Then there are just a few more of Morgan with his plants, and the very last one is his face alone in the frame, undeniably old now, his features collapsing and his hair a little windswept, but his eyes still bright and facing the lens directly.

Beneath this final photo, on another small round wooden table, the twin of the one on which the Kodak sits, is an unmarked square white envelope.

Inside, this time, there are no photos, but a single sheet of writing paper with a few lines of his looping, cursive handwriting. It reads as follows:

“To the first surviving descendent of Luisa and Frederick Mau and / or Donald and Sara Mau born after 9th February 1955 to find this letter:

“On the one and only condition, that you have not ever and will not ever enter into or profit from the Mau family business, I hereby bequeath to you this house and all of its contents as your inheritance.

“Morgan Mau, 12th January 2023.”

This is followed by a witness signature and the requisite stamps.

I stand here, looking out of the window towards the evening light on the water, and the path curving away to the right of the inlet, and I picture old Morgan Mau writing, slowly, with all the time in his world, adding with a flourish a long tail on the final 3, then the full stop, then folding it and placing it in the envelope and placing the envelope on the table. And it seems to me that he’s smiling.

Ivan Stacy teaches literature at Beijing Normal University, and has published academic work on writers including Kazuo Ishiguro, W. G. Sebald and Thomas Pynchon. He has also published fiction in the Mekong Review and is an active member of Spittoon Collective in Beijing, regularly reading at their spoken word events.